Liquidity ratios are important financial metrics that provide insight into a company’s short-term financial health and ability to meet its near-term obligations. Liquidity ratios evaluate the level of liquid or current assets available to cover a company’s current liabilities that are due within one year. A higher liquidity ratio indicates a company is better equipped to pay off debts in the short term without needing to liquidate key operating assets or raise external funding.

The current Ratio compares current assets to current liabilities to measure whether short-term resources are sufficient. The quick Ratio takes a more conservative approach by only considering the most liquid current assets. The cash ratio strictly focuses on cash and cash equivalents available. Tracking these ratios over time and comparing them to industry peers allows for meaningful analysis of trends and relative financial strength.

Maintaining adequate liquidity is important for stability. Low liquidity raises risks of defaulting on loans, disrupting cash flows, or halting operations. It also signals potential underperformance if flexibility is constrained. Therefore, liquidity ratios provide valuable insights into a company’s ability to withstand financial stress in the short run, as well as its longer-term growth prospects and investment qualities. The stability of liquidity is a reassuring sign analyzed by stock market participants.

What is a liquidity ratio?

A liquidity ratio is a financial metric that measures a company’s ability to pay off its short-term debts and obligations. The liquidity ratio evaluates the amount of liquid or current assets available to cover the company’s current liabilities that are due within one year. Liquidity ratios provide an indication of a company’s short-term financial health and liquidity position. A higher liquidity ratio indicates a more liquid and less risky financial position for the company.

Commonly used liquidity ratios include the current Ratio, Quick Ratio, and cash ratio. The current Ratio measures a company’s current assets against its current liabilities. Current assets include cash, marketable securities, accounts receivable, and inventories. Current liabilities consist of short-term debt, accounts payable, and other obligations due within one year. A higher current ratio indicates greater liquidity and a lower risk of financial distress. For most industries, a current ratio of at least 1.5 is considered financially healthy.

What is the importance of the liquidity ratio?

Liquidity ratios are important because they provide crucial insights into a company’s financial health and flexibility by measuring its ability to meet near-term obligations. Liquidity analysis helps investors assess risks, opportunities, and cash flow potential when evaluating stocks. Low liquidity signals heightened bankruptcy risks, while strong liquidity indicates financial durability and ample cash available for growth after short-term needs are met. Investors favor stocks with robust liquidity as they demonstrate flexibility to pursue opportunities even in downturns. However, poor liquidity forewarns of cash flow challenges that constrain activities that benefit shareholders, like dividends, buybacks, acquisitions, and new products.

Liquidity ratios are important because they provide key insights into a company’s financial health and flexibility. By measuring a firm’s ability to meet its near-term obligations, liquidity ratios help investors assess risks, opportunities, and cash flow potential when evaluating stocks.

First, liquidity ratios signal bankruptcy and default risk. Low liquidity means a company could struggle to pay employees, creditors, suppliers, and other short-term liabilities. This makes the stock riskier if financial distress looms. Comparing liquidity metrics to historical averages and industry benchmarks highlights improving or worsening trends. Deteriorating ratios over time or versus competitors suggest heightened financial risks that warrant caution.

For example, it points to a much higher imminent insolvency risk if a company’s current Ratio declines significantly in a year. Investors sell the stock preemptively before any credit issues. Conversely, an improving quick ratio indicates the business is accumulating more liquid assets to endure volatility. This lowered risk attracts investors and lifts the share price.

Second, liquidity ratios assess financial flexibility. Adequate liquidity shows a company has the means to pursue opportunities, invest in growth, and manage unforeseen cash needs. Illiquid firms have little margin for error and lack capital to fund expansion, R&D, marketing, and other initiatives that enhance shareholder value. Comparing liquidity between industry peers reveals which companies have greater flexibility.

Investors favor stocks with robust liquidity ratios, signaling financial durability even in downturns. Shares with poor liquidity often suffer valuation discounts due to concerns over inflexibility and constraints on cash deployment needed to lift revenues, profits, and returns.

Third, liquidity forecasts future cash flow generation potential. Since liquidity measures surplus cash after near-term obligations, it directly impacts how much cash flow remains for activities that benefit shareholders, like dividends, buybacks, capex, acquisitions, R&D, and new products. Poor liquidity forewarns of cash flow challenges ahead, jeopardizing future stock growth.

What are the common types of liquidity ratios?

Key liquidity ratios include the Current Ratio, Quick Ratio, Cash Ratio, Net Working Capital Ratio, Net Debt Ratio, Days Sales Outstanding, Absolute Liquidity Ratio, Basic Defense Ratio, Basic Liquidity Ratio, Times Interest Earned Ratio, and Inventory Turnover Ratio. These track metrics like a firm’s current assets versus current liabilities, cash and equivalents, accounts receivable turnover, operating cash flow, and inventory management efficiency.

1.Current Ratio

The current Ratio is a liquidity ratio that measures a company’s ability to pay short-term obligations or those due within one year. It compares a firm’s current assets to its current liabilities. Current assets include cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and other assets that are expected to be converted to cash in the next 12 months. Current liabilities consist of short-term debt, accounts payable, and other obligations due within one year.

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

For example, suppose a company has Rs.2 million in current assets and Rs.1 million in current liabilities; its current Ratio would be as given below.

Current Ratio = Rs.2,000,000 / Rs.1,000,000 = 2

A current ratio of 2 means the company has twice as many current assets as current liabilities. This indicates it is in a good position to cover its short-term obligations. A ratio under 1 means current liabilities exceed current assets, and there are problems with liquidity.

2. Quick Ratio

The quick Ratio, also known as the acid-test Ratio, is a liquidity ratio that measures a company’s ability to pay its short-term obligations with its most liquid assets. It compares a firm’s high-quality liquid assets to its current liabilities. The quick Ratio only considers cash and cash equivalents, accounts receivable, and marketable securities as liquid assets, excluding inventory and other assets.

Quick Ratio = (Cash and Cash Equivalents + Accounts Receivable + Marketable Securities) / Current Liabilities

For example, suppose a company has Rs.100,000 in cash, Rs.80,000 in accounts receivable, Rs.50,000 in marketable securities, and Rs.150,000 in current liabilities; its quick Ratio would be as given below.

Quick Ratio = (Rs.100,000 + Rs.80,000 + Rs.50,000) / Rs.150,000 = 1.3

A quick ratio of 1.3 means the company has Rs.1.30 of highly liquid assets available to cover each Rs.1 of current liabilities. This indicates it is in a strong position to meet its short-term obligations without needing to sell inventory or other assets. A ratio under 1 indicates potential liquidity issues.

3. Cash ratio

The cash ratio is the most conservative liquidity ratio. It measures a company’s ability to repay its current liabilities with only cash and cash equivalents. Cash equivalents are assets that are quickly converted into cash, such as Treasury bills and short-term certificates of deposit. The cash ratio excludes receivables and inventories.

Cash Ratio = (Cash and Cash Equivalents) / Current Liabilities

For example, suppose a company has Rs.50,000 in cash, Rs.20,000 in T-bills, and Rs.100,000 in accounts payable; its cash ratio would be as given below.

Cash Ratio = (Rs.50,000 + Rs.20,000) / Rs.100,000 = 0.7

This means the company has Rs.0.70 of cash and cash equivalents available to cover each Rs.1 of current liabilities. A lower ratio indicates potential liquidity problems, while a higher ratio provides a cushion for paying obligations. Most analysts consider a cash ratio above 1 to be very liquid. A ratio under 0.5 indicates concern about the company’s solvency.

4. Net working capital ratio

The net working capital ratio measures a company’s liquidity and its ability to meet short-term obligations. It looks at the difference between current assets and current liabilities. Current assets are cash, inventory, accounts receivable, and other assets that are converted to cash within a year. Current liabilities are obligations that must be paid within one year.

Net Working Capital Ratio = (Current Assets – Current Liabilities) / Total Assets

For example, suppose a company has Rs.500,000 in current assets, Rs.300,000 in current liabilities, and Rs.1,500,000 in total assets; its net working capital ratio would be as given below.

Net Working Capital Ratio = (Rs.500,000 – Rs.300,000) / Rs.1,500,000 = 0.13

A positive ratio indicates the company pays its short-term obligations after liquidating current assets. A higher ratio signifies greater liquidity. A negative ratio means current liabilities exceed current assets and indicates financial distress. The ideal Ratio depends on the industry.

5. Net debt ratio

The net debt ratio measures a company’s leverage and ability to pay all its debts with its assets. It compares a company’s total debt to its total assets to show how leveraged it is. Total debt includes all short-term and long-term liabilities. Total assets encompass current assets and long-term assets like property, plant, and equipment.

Net Debt Ratio = Total Debt / Total Assets

For example, suppose a company has Rs.2 million in total debt and Rs.5 million in total assets; its net debt ratio is given below.

Net Debt Ratio = Rs.2,000,000 / Rs.5,000,000 = 0.4

This means the company’s debt is 40% of its total assets. A ratio greater than 1 means the company has more debts than assets, which indicates high risk. A lower ratio is more favorable. However, an extremely low ratio like 0.1 indicates the company is not optimizing its use of leverage. The ideal Ratio varies by industry.

6. Days sales outstanding (DSO)

Days sales outstanding (DSO) measures the average number of days it takes a company to collect payment from its credit sales. It shows how efficiently a company manages its receivables or how quickly customers pay their debts.

DSO = (Average Accounts Receivable / Total Credit Sales) x Number of Days

For example, suppose a company has an average accounts receivable of Rs.1 million, annual credit sales of Rs.5 million, and the year has 360 days; its DSO would be as given below.

DSO = (Rs.1,000,000 / Rs.5,000,000) x 360 = 72 days

This means the company takes around 72 days on average to collect its receivables. A lower DSO indicates an efficient collection process, while a higher DSO signifies slower payment. However, an extremely low DSO like 5 could mean the company’s credit terms are too stringent. The ideal DSO varies by industry but is often between 30-90 days.

7. Absolute liquidity ratio

The absolute liquidity ratio measures a company’s ability to pay off its short-term liabilities using only cash and cash equivalents, the most liquid assets. Cash equivalents are investments that are quickly converted to cash, such as Treasury bills. The absolute liquidity ratio excludes receivables and inventory.

Absolute Liquidity Ratio = (Cash and Cash Equivalents) / Current Liabilities

For example, suppose a company has Rs.50,000 in cash, Rs.20,000 in Treasury bills, and Rs.80,000 in accounts payable; its absolute liquidity ratio is given below.

Absolute Liquidity Ratio = (Rs.50,000 + Rs.20,000) / Rs.80,000 = 0.875

This means the company covers 87.5% of its short-term liabilities with its most liquid assets. A higher ratio indicates greater liquidity, while a lower ratio suggests potential trouble meeting obligations. A ratio under 1 means current liabilities exceed liquid assets on hand. Most analysts prefer to see a ratio of at least 1 or higher for financial stability.

8. Basic defence ratio

The basic defense ratio measures the ability of a nation’s military forces to defend its territory by comparing active military personnel to the size of the country. It is calculated by dividing the number of active duty military members by the total land area of the country.

Basic Defence Ratio = Active Military Personnel / Total Land Area

For example, suppose a country has 1,000,000 active duty military personnel and a total land area of 3,000,000 square kilometers; its basic defense ratio would be as given below.

Basic Defence Ratio = 1,000,000 / 3,000,000 = 0.33

This means there are 0.33 active military members per square kilometer of land. A higher ratio indicates a greater military presence and defense capability relative to the size of the nation. A lower ratio suggests potential vulnerabilities. The ideal Ratio depends on a country’s defense strategy and perceived security threats. Most analysts consider a ratio above 0.5 to provide a strong territorial defense capability.

9. Basic liquidity ratio

The basic liquidity ratio measures a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations with its most liquid assets. It compares cash and cash equivalents to current liabilities. Cash equivalents are assets that are quickly converted into cash, such as Treasury bills and short-term certificates of deposit. Current liabilities are financial obligations due within one year.

Basic Liquidity Ratio = (Cash and Cash Equivalents) / Current Liabilities

For example, suppose a company has Rs.50,000 in cash, Rs.20,000 in T-bills, and Rs.100,000 in accounts payable; its basic liquidity ratio would be as given below.

Basic Liquidity Ratio = (Rs.50,000 + Rs.20,000) / Rs.100,000 = 0.7

This means the company has 70 cents in liquid assets available to cover each Rs.1 of its short-term liabilities. A higher ratio indicates greater liquidity and the ability to pay obligations as they come due. A ratio under 1 suggests potential trouble meeting short-term debts with cash on hand. Most analysts prefer to see a basic liquidity ratio of at least 1.

10. Times interest earned ratio

The time’s interest earned Ratio, also called the interest coverage ratio, measures a company’s ability to pay its interest expenses. It compares earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) to the company’s interest payments due in a given period. A higher ratio indicates greater financial flexibility to cover interest costs.

Times Interest Earned Ratio = EBIT / Interest Expense

For example, suppose a company has an EBIT of Rs.1 million, and its quarterly interest expense is Rs.200,000; its time’s interest earned Ratio would be as given below.

Times Interest Earned Ratio = Rs.1,000,000 / Rs.200,000 = 5

This means the company has earnings 5 times greater than its interest obligations. A ratio under 1 suggests the company has trouble covering interest costs. A ratio under 2 could indicate a higher risk of default. Most analysts prefer to see a ratio of at least 2 or 3 for stability. However, an extremely high ratio, like 10 or 20, could mean the company has too little leverage and is not optimizing assets.

11. Inventory turnover ratio

The inventory turnover ratio measures how efficiently a company manages its inventory and how quickly inventory is sold. It compares the cost of goods sold to the average inventory for a period. A higher turnover ratio indicates greater efficiency in selling inventory and better liquidity.

Inventory Turnover Ratio = Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory

For example, suppose a company has Rs.2 million in cost of goods sold and an average inventory of Rs.500,000; its inventory turnover ratio is given below.

Inventory Turnover Ratio = Rs.2,000,000 / Rs.500,000 = 4

This means the company turns over its inventory 4 times per year. A low turnover like 1 or 2 could mean excess inventory and increased costs. A very high ratio, like 10+, indicates inadequate inventory levels and lost sales. The ideal Ratio varies by industry, but a ratio of 5-8 is generally considered positive. Comparing the Ratio to peers provides a better context for evaluating inventory management.

What is an example of liquidity ratio calculation?

Reliance Industries is an Indian multinational conglomerate company headquartered in Mumbai, Maharashtra. In the financial year 2023, the company reported total current assets of ₹2,55,996 crore, which increased by 2.2% from the previous financial year. The total current liabilities for the year stood at ₹2,37,691 crore, reflecting an increase of 8.5% from fiscal year 2022.

An analysis of Reliance Industries’ liquidity ratios for FY23 shows that the current Ratio stood at 1.07. This suggests that the company can technically cover its short-term liabilities with its current assets. However, the Ratio is just barely above the threshold of 1.0, which is generally considered safe for most industries. This indicates a need for Reliance to continue monitoring and potentially improving its short-term debt management.

The quick ratio for the year was 0.68, which remains a concern as it highlights the potential difficulty in settling immediate obligations without selling other current assets. This reinforces the need for Reliance to bolster its immediate liquidity reserves. The cash ratio was recorded at 0.82, showing a positive improvement over previous years. However, it is still not ideal, and Reliance should consider strategies to build up its readily available cash further.

What are the factors that affect the liquidity ratio?

The major factors that affect liquidity ratios are economic conditions, inventory efficiency, market sentiment, accounts receivable/payable management, cash flow management, and creditworthiness.

The overall state of the economy has a major influence on liquidity. During strong economic growth, companies tend to have higher revenues and profits. This provides more internal cash flow to pay obligations. Conversely, in recessions, profits decline, and liquidity suffers. Investors in the stock market closely watch economic trends and forecasts. Investors tend to sell shares of companies with weak liquidity if a recession is expected. This reduces their stock price and valuation.

The size and turnover rate of a company’s inventory impacts working capital and liquidity. Having too much-unused inventory ties up cash and reduces liquidity. It also raises costs for storage and maintenance. Companies want to avoid excess inventory but still maintain enough stock to fill orders. Managing inventory is a balancing act. Publicly traded companies need to demonstrate to stock investors that inventory is optimized for maximum efficiency and liquidity.

Investor sentiment and expectations in the stock market influence liquidity. They will likely buy shares and increase their stock price if investors are optimistic about a company’s outlook. The higher valuation provides more flexibility to issue new shares or bonds if needed to raise cash. However, negative market sentiment has the opposite impact. Bearish investors will sell shares, driving down the stock price. This increases the cost of obtaining new capital. Managing investor perceptions is crucial for maintaining liquidity.

The timing of payments for sales and purchases affects short-term cash flow. A company wants to collect receivables from customers as soon as possible after a sale. This accelerates cash inflows. However, suppliers prefer slower payment cycles to maintain their own liquidity. Public companies must find an optimal balance for receivables and payables cycles. Stock investors want to see efficient management of working capital through prudent credit terms. This demonstrates fiscal discipline to the market.

Cash management involves forecasting short-term cash needs and sources. It also requires policies for optimal investment of excess cash. Public companies use cash management strategies to avoid holding too much idle cash while still retaining enough for liquidity needs. Stock investors recognize that high cash levels reduce return on assets. Cash management links closely with inventory and working capital policies to keep liquidity at appropriate levels.

What are the limitations of the liquidity ratio?

The limitations of the liquidity ratio are that it provides only a snapshot of liquidity, does not account for upcoming liabilities, ignores asset quality, lacks industry and business model context, and focuses too narrowly on high liquidity as ideal.

The liquidity ratio is based only on balance sheet data at a single point in time. However, a company’s cash and liquid assets fluctuate significantly throughout a financial reporting period. As long as a company has strong liquidity on the day the balance sheet is reported, it does not mean it maintains that liquidity throughout the entire quarter. There could be periods of strained liquidity that this Ratio fails to reveal. Investors should keep in mind that it shows only a snapshot, not ongoing liquidity management.

In addition, the liquidity ratio does not consider upcoming liabilities and cash outflows in the near future that are not yet on the balance sheet. Companies often have major cash commitments soon after the balance sheet date, such as loan repayments, supplier payments, scheduled capital expenditures, and more. These known upcoming obligations quickly reduce liquidity, even if the Ratio calculated on the balance sheet date appeared positive. By not accounting for these near-term liabilities, the liquidity ratio underestimates true liquidity risk.

The liquidity ratio also treats all liquid assets as equal, regardless of asset quality. However, some assets are restricted, inaccessible, illiquid, or unable to be converted to cash quickly. Cash trapped overseas or set aside for special purposes is not available to meet everyday obligations. Inventory that is obsolete or difficult to sell reduces realizable assets below what the Ratio implies. The same goes for accounts receivable that are unlikely to be collectible. Failing to consider asset quality limits the usefulness of this metric.

In addition, comparing liquidity ratios between companies is problematic. Different industries, such as retail or construction, tend to have very different liquidity ratios in their normal course of business. And companies with different business models and working capital needs are not comparable. Using the liquidity ratio without context could lead investors to make inaccurate judgments about relative liquidity strength.

Another limitation is that the liquidity ratio focuses narrowly on cash and liquid assets. However, holding high levels of low-yielding cash will drag on company returns. Having very high liquidity is not always optimal either. So, while liquidity is certainly important, investors should keep the bigger picture in mind rather than assuming that a higher liquidity ratio is inherently better.

What is a good liquidity ratio?

For investors, a high liquidity ratio is generally preferred as it demonstrates that the company readily converts assets into cash in order to pay off current liabilities if needed. A ratio between 1.0 and 1.5 is usually considered a good liquidity ratio for most businesses.

A ratio of 1.0 means current assets cover current liabilities exactly, and anything above 1.0 provides an additional liquidity cushion. For some industries that require large inventory, like retail, a slightly lower ratio, around 0.8, could be acceptable. On the other hand, anything below 1.0 indicates potential trouble in paying bills and expenses. An extremely high number above 2.0 could signal inefficient use of capital with excess cash sitting idly. Therefore, investors typically look for companies with liquidity ratios in the ideal range of 1.0 to 1.5.

What is a bad liquidity ratio?

A liquidity ratio below 1.0 means a company’s current liabilities exceed its current assets. This indicates the company is not able to readily convert assets into cash in order to pay off pressing short-term bills and debts. The lower the Ratio, the greater the risk that the company could default on obligations, declare bankruptcy or experience severe disruptions to its operations from insufficient cash flow.

For investors, an unhealthy liquidity ratio below 1.0 is a sign of substantial risk. It means the company is struggling with liquidity, and its precarious financial position leaves little room for flexibility in the face of economic downturns, unexpected costs, or loss in sales. These companies are highly vulnerable to market conditions, and any slight change could jeopardize their ability to function.

These high-risk companies become entirely dependent on selling assets or taking on new debt to generate liquidity as their revenues fail to sufficiently cover short-term obligations. This dependency exacerbates the problem over time. Furthermore, a lack of liquidity means the company needs to cease vital functions like R&D, marketing, or growth initiatives in order to cover basic operating expenses.

Investors will compare a company’s liquidity ratio against industry averages to better evaluate its position. While 0.9 is below average in one industry, 0.7 could be catastrophic in another. However, any ratio persistently below 1.0 merits concern for stock investors. It demonstrates the company’s inability to operate efficiently and convert assets into cash flow.

Can the Liquidity Ratio be negative?

No, the liquidity ratio cannot be negative. The liquidity ratio is a measure of a company’s ability to pay off its short-term debts and obligations. It looks at the company’s current assets that are quickly converted to cash and compares that to the company’s current liabilities or debts due within the next year. Since both current assets and current liabilities are positive values, the liquidity ratio is always expressed as a positive number.

A higher liquidity ratio indicates a company is more liquid and has a greater ability to meet its short-term obligations. A liquidity ratio below 1 means a company’s current liabilities exceed its current assets, and it has trouble meeting short-term obligations if current assets cannot be quickly converted to cash. However, the Ratio cannot go negative as the assets and liabilities are not negative values. Even if a company has zero current assets, the ratio ratio would be 0, which is not a negative number.

What is a statutory liquidity ratio?

The statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) is a reserve requirement that commercial banks in India need to maintain in the form of liquid assets like cash, gold, or other approved securities. The Ratio was introduced in India in 1963 and is set by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The SLR aims to control the expansion of bank credit and secure the safety of depositors’ money. It ensures that a portion of bank deposits is invested in liquid assets that can readily be converted into cash to meet any repayment obligations. The statutory liquidity ratio is an essential tool in the RBI’s arsenal to control inflation and prop up the Indian rupee.

Originally, the RBI set the SLR at a high level of 38.5% of a bank’s total demand and time liabilities. This meant banks had to invest over a third of their deposits into approved government securities and other liquid assets. Over the decades, the RBI has steadily reduced the SLR to manage market liquidity conditions. In its bi-monthly monetary policy of February 2020, the RBI slashed the SLR to 18% – the lowest level since the Ratio was introduced.

The uptick or reduction in the SLR directly impacts the availability of loanable funds in the economy. A higher SLR sucks out liquidity from the system as it forces banks to maintain a larger cash reserve. This, in turn, leaves them with less money for lending. Conversely, a lower SLR injects liquidity into the system.

What is a liquidity coverage ratio?

The liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) is a metric used to evaluate the short-term liquidity position of financial institutions such as banks and brokerage firms. It measures whether a firm has sufficient high-quality liquid assets to cover expected cash outflows in a 30-day stressed environment. Maintaining an adequate LCR is crucial for these institutions to survive periods of market turbulence.

In the stock market, brokerage firms act as intermediaries facilitating trading and lending of securities on behalf of clients. One of their key risks is liquidity risk – the risk of not having enough liquidity to fulfill client orders or borrowing demands. The LCR framework helps brokerages mitigate this risk. An LCR below 100% implies that the brokerage does not have enough liquid buffers to handle sudden client withdrawals or margin calls under stress. In times of market volatility, like crashes or bubbles, many clients want to sell securities urgently and withdraw funds quickly.

Margin lending to clients also carries the risk of margin calls due to falling stock prices. All this creates huge liquidity pressures on the brokerage within a short period of 30 days or less. Maintaining a higher LCR over 100% enables brokerages to tide over these liquidity squeezes. Brokerages meet client demands for paying out-of-sale proceeds or additional margin requirements without forcing asset fire sales. Having sufficient high-quality liquid assets as a buffer prevents brokerage operations from freezing up in crisis situations.

Some assets counted towards the LCR include cash, central bank reserves, high-rated government securities, and corporate bonds. These assets are readily converted into cash in private markets to meet outflows. The LCR does not include equities or low-rated bonds, which face liquidity risks themselves. The components and calculations of the LCR for brokerage firms are similar to those of banks. Regulators track LCR levels closely to monitor brokerage health and prevent systemic liquidity risks. They enforce higher LCR requirements on large brokerages or those heavily into proprietary trading and derivative exposures. Brokerages occasionally need to raise capital through share issuance or debt to bolster their liquidity coverage ratios. Having a robust LCR above fully-phased-in requirements provides a further cushion against market turbulence.

What are some other useful ratios besides liquidity ratios?

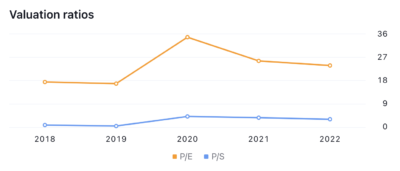

Five useful financial ratios besides liquidity ratios are profitability ratios, leverage ratios, valuation ratios, efficiency ratios, and market value ratios.

Profitability ratios like return on assets, return on equity, and profit margin show how efficiently a company is generating profits from its operations. Leverage ratios such as the debt-to-equity ratio indicate the degree of financial leverage and long-term solvency. Operating ratios like the asset turnover ratio and inventory turnover ratio measure how well assets are being utilized to generate revenues. Finally, valuation ratios like the price-to-earnings ratio and price-to-book Ratio assess the valuation of a company’s stock price compared to financial metrics like earnings and book value.

Together, these various ratios provide a more complete picture of a company’s financial position and operating performance when evaluating its stock as an investment. Using a mix of liquidity, profitability, leverage, operating, and valuation ratios allows investors to thoroughly analyze a company from multiple angles.

What’s the difference between liquidity ratio & solvency ratio?

Liquidity and solvency ratios are two important classes of financial ratios used to assess the health and stability of companies, especially financial institutions like brokerages. While liquidity ratios evaluate the short-term financial situation, solvency ratios evaluate the longer-term financial sustainability and risks.

Liquidity ratios measure whether a company has sufficient liquid assets to cover its short-term liabilities and near-term obligations. For brokerages, liquidity is crucial to meet client cash withdrawals, trading settlement dues, and margin calls in a timely manner during periods of market volatility. Common liquidity ratios are the current Ratio and Quick Ratio.

Current Ratio measures if current assets are adequate to repay current liabilities. Anything below 1 indicates potential issues in repaying short-term obligations. Quick Ratio is more conservative as it only considers absolute liquid assets, ignoring inventory and receivables. The cash coverage ratio specifically measures whether a brokerage has enough cash to meet margin calls.

On the other hand, solvency ratios assess a company’s ability to fulfill long-term obligations and the size of its leverage risk. They indicate if the company has taken on too much debt, it turns unsustainable. For brokerages, solvency means having enough capital to absorb trading losses, loan defaults, and operational risks over an extended period of time.

Key solvency ratios are the debt-to-equity Ratio and interest coverage ratio. A high debt-to-equity ratio indicates the brokerage has a risky amount of debt relative to its equity capital. The interest coverage ratio measures how easily a brokerage service receives its interest costs from operating income. A lower ratio suggests a high risk of loan default.

While liquidity is about short-term cash management, solvency evaluates long-term balance sheet stability. A company is solvent but faces temporary liquidity issues due to poor working capital management. On the other hand, it is possible for a company to be liquid but highly leveraged, threatening its solvency.

Regulators keep a close watch on both the liquidity and solvency of systemically important brokerages. Liquidity issues of one large brokerage quickly spiral into wider market instability. Inadequate solvency also leads to insolvency and collapse. Tighter regulations have enforced higher capital and liquidity requirements on brokerages after the 2008 financial crisis.

Brokerages need to carefully manage their leverage, borrowing sources, and asset-liability profile to maintain both solvency and liquidity. Having sufficient high-quality liquid assets as a percentage of net outflows provides a liquidity buffer. Conservative financial leverage, diversified funding sources, and adequate capital cushions safeguard solvency.

Striking an optimal balance between liquidity and solvency is vital for a brokerage’s stability. Excessive focus on liquidity limits business growth and profitability. On the other hand, pursuing higher returns through increased leverage compromises solvency. The business model also influences suitable liquidity and solvency levels for a brokerage.

Where is liquidity on a balance sheet?

Liquidity is present on a balance sheet in the form of assets that are quickly converted to cash. Current assets like cash, marketable securities, accounts receivable, and inventory are considered liquid assets. Cash, being the most liquid asset on the balance sheet, is already in cash form and can immediately be used to pay off short-term liabilities if needed. Marketable securities, like stocks and bonds, are quickly sold and converted to cash. Accounts receivable reflects money owed to the company by customers for goods or services, which is expected to be paid within a short period of time. Finally, inventory includes finished goods, raw materials, and works-in-progress that the company intends to sell as part of normal business operations. Though not as liquid as cash, inventory typically is sold to generate cash relatively fast.

The more liquid assets a company has, the better able it is to meet its short-term obligations as they become due. Current liabilities like accounts payable, short-term debt, and accrued expenses reflect near-term financial obligations. The Current Ratio, which divides current assets by current liabilities, measures a company’s liquidity and its ability to pay off debts within the next year. A higher current ratio indicates stronger liquidity and financial health. Tracking liquidity over time is important to assess the financial position and health of a business.

Is liquidity ratio helpful in fundamental analysis?

Yes, liquidity ratios like the current Ratio and quick Ratio are indeed useful metrics for the fundamental analysis of stocks. These ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations and give investors an idea of its short-term financial health. A high level of liquidity means a company readily converts assets to cash to pay off debts, while low liquidity could be a sign of potential trouble meeting liabilities. While evaluating stocks, investors want to see consistent, healthy liquidity ratios over time.

Trends of declining liquidity could signal future difficulties for the business. As such, analyzing liquidity ratios helps investors assess financial risks and the overall stability of a company as part of a thorough fundamental analysis when researching stock investments. Liquidity metrics provide valuable insight into a company’s financial position.